The UX of Getting Laid Off

So getting laid off has exposed me to some truly user-hostile user experience design from companies who know their users can’t leave. That’s been fascinating (and a little infuriating) coming from the world of Department of Defense design, where people have been dealing with hostile interfaces for years simply because they have no choice. In that ecosystem, Byzantine processes and locked-in contracts mean you get what you get. I’ll come back to the DoD angle in a future post, but for now I want to talk about the civilian version of the same problem.

Two of the clearest examples have been rolling over my 401(k) and signing up for COBRA. My 401(k) was with Voya, and literally every link about rolling it over out of Voya was broken. Rolling it into a Voya IRA? That link worked just fine. But the link with instructions for rolling over to an external plan hit a Cloudflare error. It was the only URL I could find on that domain throwing Cloudflare issues, despite using the exact same domain and subdomain.

Digging deeper didn’t help. Other rollover-related links simply didn’t work. Links around them—including, again, the ones for opening a Voya IRA—were humming along without issue. To be fair, the Cloudflare problem was resolved later in the day, but those other rollover links stayed unclickable.

Now, rolling over a 401(k) is a serious first-world problem. I recognize the privilege in even having retirement savings. Worst-case scenario, I leave the money where it is and still get the benefit. But that’s exactly the point: there’s zero incentive for Voya to make it easy for me to leave, so they don’t.

The second obstacle is less of a first-world problem: COBRA. Since the U.S. is the only developed nation without universal healthcare, the whole process feels like navigating a bureaucratic maze. COBRA is the “generous” government-mandated option that lets you keep your old insurance while putting you on the hook for the full premium.

Different plans use different portals (some apparently have no portal at all), but mine was through ADP. The entire experience was full of user-hostile decisions. I’m in a fortunate position—no one in my family currently needs expensive medication or a planned procedure—but plenty of people facing COBRA are under real pressure. Those are the users who need the best UX, and like Voya, ADP has no incentive to make this easy. What are you going to do—comparison-shop for COBRA? So you get what you get.

You get this big packet in the mail—16 pages long—and buried on page 13 is the line, “As we previously shared, our self-service member portal is an integral part of our new service offering.” Reader, I went back through the 13 pages. I scanned them, ran OCR, and even had an LLM review them. There was no mention of a self-service portal anywhere. Then it gets better. The instructions say, “Visit [website], click ‘New User.’” Here’s the home page: no New User link or button to be found. Now imagine someone stressed, not especially technical, trying to keep their health insurance. A 12-point font with a link color failing WCAG AA at 3.04:1. And just for fun, the landing page weighs 1.5 MB compressed and 7.7 MB uncompressed.

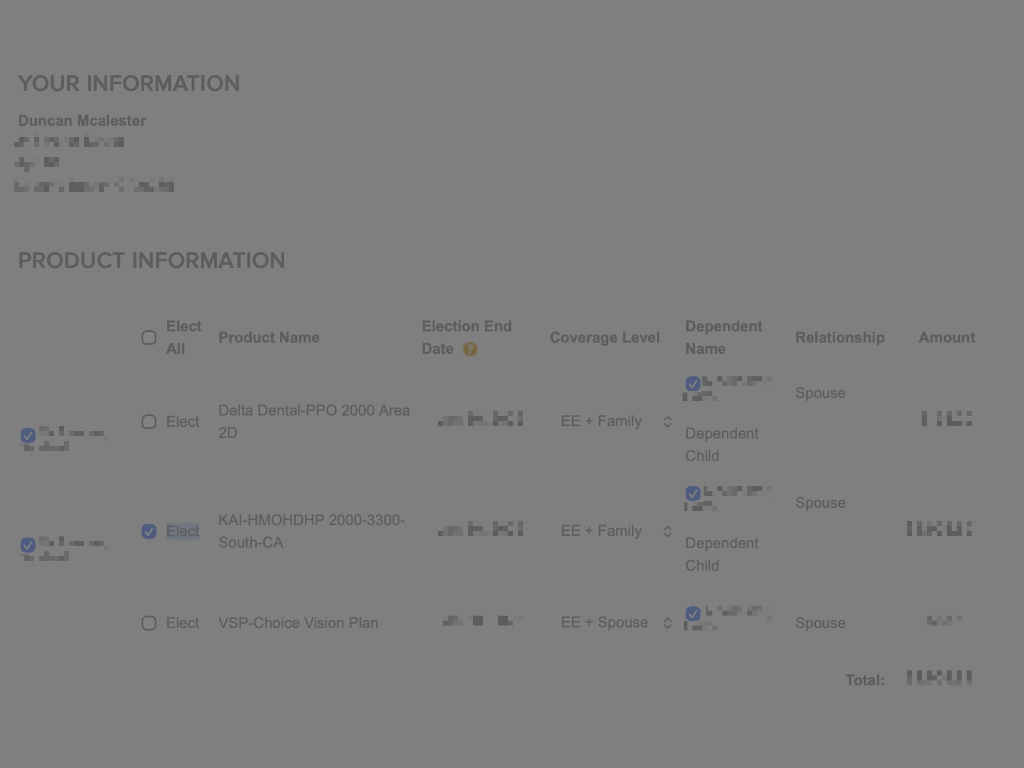

The second issue was worse: the table. A full mess. Cells misaligned, nested tables breaking out of their containers, label columns collapsing. I had to grab the raw HTML and apply my own CSS just to read it, and even then it looked like something dug out of a server that hadn’t been rebooted since 2009.

The UX and copy around the table also feel overly final, as if clicking the wrong checkbox will instantly enroll you in a $2,000-per-month plan or, worse, leave you uninsured. That’s not how COBRA actually works—you can opt in and out at certain points—but the UI frames every choice like a trapdoor.

All of these frustrations point to the same core issue: these systems aren’t designed for people with choice. They’re built for compliance, cost control, and keeping the lights on. And when the organization has no incentive to improve the experience, the experience doesn’t improve.

I’m trying to be better these days about not stopping at the complaint. Complaining is easy; solutions take work. And in systems built for captive users, the hardest part is accepting that no one else is coming to fix it.

There are no KPIs for this work. Nobody is getting a shout-out at the quarterly all-hands for fixing a paragraph on a page no one has looked at in half a decade. Captive-user UX rarely gets an executive sponsor, a roadmap slot, or a budget. Yet these experiences often matter the most, because the people using them have no alternatives.

It reminds me of a quote from Barack Obama:

You see, the challenges we face will not be solved with one meeting in one night. Change will not come if we wait for some other person or some other time. We are the ones we've been waiting for. We are the change that we seek.

If we’re the ones we’ve been waiting for

, where do you start. I don’t think these are revolutionary ideas, but they are largely actionable.

- Know whether your users have choice

- If you’re building for captive users, your responsibility increases. They can’t walk away.

- Take ownership of the neglected corners

- Start with something tiny and make it 1% better. Fix a label. Rewrite a sentence. Make sure the terminology in the UI matches the documentation. These small repairs compound and ripple outward.

- Go spelunking in your own product

- Use it the way your users do. Not all UX debt needs a months-long research phase. Sit down and use the product.